Sheet-metal gutter linings, whether made of copper, lead or both, are relatively involved and require the services of a highly skilled artisan craftsman.

In “Traditional Rainwater Conductor Systems of the 18th and 19th Centuries,” Karen Dodge of the U.S. National Park Service, Washington, D.C., states built-in gutters were first adopted in North America during the 18th century in high-style Georgian and Federal-style buildings, usually institutional or commercial, where refined architectural qualities were desired. Although built-in gutters are highly functional, they also serve an aesthetic purpose. As structures were erected in the classical order with elaborate cornices and entablature, it became necessary to collect and channel rainwater without detracting from the architectural character of the building. Built-in gutters served this function well, hidden from sight and shedding water to the exterior.

Built-in gutters, today, are typically constructed in the same manner as they have been since the 18th century. They are wooden boxes with bottoms sloped toward the outlets where water is drained to leaders, or conductor pipes, that channel the water away from the building. The first gutters in this style were actually troughs or box gutters, carved out of wood and rubbed with linseed oil or painted to protect the wood. Corners and seams were bonded with lead wedges. Needless to say, maintenance was critical to their success or failure. Later, the advent of sheet lead allowed for broader gutters, as linings covered the wooden troughs. By the end of the century, copper became available in the U.S. and a popular choice for gutter linings because of its durability and the functional nature of the material in a sheet-metal application.

INSPECTION AND MAINTENANCE

The most common sign of water penetration is peeling paint and decay in the wood soffit under the gutter. Other signs are dark stains and mildew or deterioration of masonry. Water infiltration may be visible in attic spaces or areas beneath the gutters where plaster and other interior finishes evidence water damage. The sooner a leak or area vulnerable to failure is addressed, the smaller the scope and cost of repairs. Cleaning out leaves and debris from gutters as often as necessary is essential for durability and proper performance.

Careful inspection by a competent roofer is critical to the longevity and success of the system. He or she will look for defects, such as localized damage caused by fallen limbs or other debris, cracks from expansion and contraction at joints or folds, or pinholes from corrosion. Roofing tar and other bituminous compounds should never be used to patch, repair or coat gutter linings. It makes the condition of the gutter indeterminable, corrodes metal linings, will crack and fail quickly, and cannot be removed without destroying the lining. Ice damming is not uncommon in the winter but should not be removed with sharp tools for obvious reasons.

When tin or terne-coated steel gutter linings fail, water intrusion will occur and cause wood rot. Eventually, architectural details will be lost and replacement will be necessary.

RESTORATION

Restoration of long-neglected built-in gutter systems that leak and have caused decay in the cornice and roof structure is often complicated and can be costly. But once the work is completed, a regularly maintained, well-detailed system can last 60 to 100 years or more, depending on the life of the metal lining. A preservation architect or consultant should inspect the building, propose treatment options, develop working drawings and specifications, and supervise bidding and construction. Temporary protection and permanent repairs should be performed by a roofer experienced in this specialty on historic buildings.

“We encourage restoration of historic built-in gutter systems,” says Michael Devonshire, a building conservator and principal at Jan Hird Pokorny Associates, New York. “The use of modern building materials as an adjunct to traditional materials boosts longevity.” Devonshire states the typical steps involved with a built-in gutter restoration involve:

- Removing the gutter lining and 2 feet of the roof covering above the curbing of the gutter.

- Repairs to rotted or otherwise deteriorated frame work. Where rafter ends or lookouts are rotted, install sisters (new rafter ends adjacent to old ones) or scarf in new wood and sisters.

- Replacing the old wooden gutter bottom with a sustainable wood material, such as cedar or kilndried- after-treatment (KDAT) plywood. KDAT is treated for resistance to decay, minimal expansion and contraction, and increased longevity.

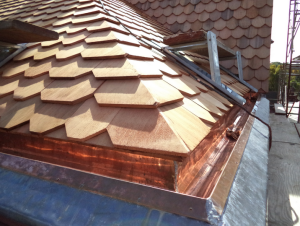

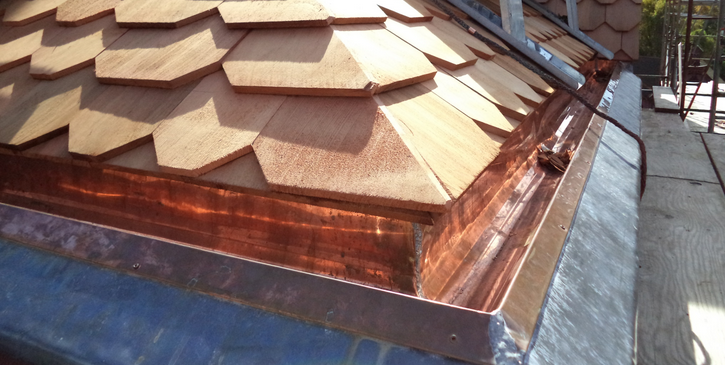

- Installing the gutter lining: an elastomeric ice-and-water shield on the bottom (not always required); building felt; a slip-sheet of rosin paper; and copper on top (16 or 20 ounce, depending on the dimensions of the gutter).

- Installing the roof covering on the roof deck above the gutter. This includes 2 feet of elastomeric ice-and-water shield (or copper flashing) beneath.

- Repairing or replacing cornice mouldings, brackets and other architectural woodwork.

PHOTOS: WARD HAMILTON

Be the first to comment on "Built-in Gutters Should Be Carefully Inspected, Restored and Maintained"