-

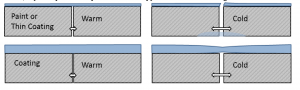

Elongation is the measure of a sample, typically 1-inch long, stretched some multiple of its original size. A 100 percent (at 73 F/23 C) value means that a 1-inch sample can elongate to a maximum of 2 inches under an ideally balanced load, before rupture. Measured at the same time is the tensile strength, or breaking resistance, with that same ideally balanced load, measured in accepted units of force. To ensure consistency and repeatability, the samples are prepared under ideal controlled conditions. The problem with this is, in the real world, bridging most often occurs when the contraction of materials is caused by very cold temperatures. This is why low-temperature flexibility is included in most ASTM material standards. A coating that will crack under such conditions may also peel up at the edges of a joint when it ruptures. Those that possess excellent flexibility, even down to -35 F/-31 C, will maintain their protective properties in any climate. The flexibility test is normally coupled with a weathering or accelerated-aging test to confirm that barrier properties will remain for many years of use.

Tensile strength interacts with a number of important performance concerns but by itself doesn’t reveal much. A roof coating is not a rope or a chain to be assessed merely for breaking strength. Instead, we need to know that it will resist typical roofing loads. As such, tensile and elongation are best evaluated together. If both are high, the coating is likely formulated with less filler and more resin. A combination of high tensile, high elongation and good low-temperature flexibility indicates a higher-quality material.

Tear strength is often a part of ASTM material standards because stresses on roofs are not ideal balanced loads and coating films are never flawless. All coatings have voids and thin spots that cover stress points, like seams, metal joints or fastener heads, where tears propagate, making tear strength the limiting strength property for measuring crack bridging capabilities.

The role of film thickness is tied to the effective elongation a coating provides.

Liquid-applied Membranes

The current working definition within ASTM Subcommittee D08.25 on Liquid Applied Polymeric Materials Used for Roofing and Waterproofing Membranes that are Directly Exposed to the Weather includes the assumption that a fabric or reinforcement be used to create a membrane “system.”

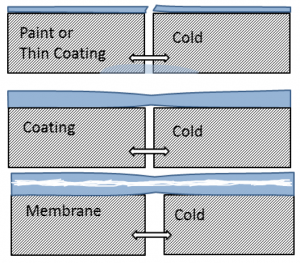

The current working definition within ASTM Subcommittee D08.25 on Liquid Applied Polymeric Materials Used for Roofing and Waterproofing Membranes that are Directly Exposed to the Weather includes the assumption that a fabric or reinforcement be used to create a membrane “system.” Why is this good practice? It returns to tear strength and the way mechanical stresses are distributed through the film.

A typical coating may have an extrapolated tear strength of 60 pounds at a theoretical 1-inch thickness, but at a more realistic 20 mils that same coating will have a minimal gross tear strength of only 1.2 pounds. Yet, if that same coating is embedded in a reinforcement fabric, the fabric alone will often have a tear strength above 4 pounds—even at its weakest point—and will average above 20 pounds. The reinforcing properties of the fabric will dominate the performance characteristics of the membrane system, distributing stress in the same way a thicker coating does but much more effectively.

For example, an ASTM D6083 acrylic coating applied at 25 mils will have an elongation of over 100 percent but a gross tear strength of only 1.5 pounds. When reinforced, elongation may drop down to about 35 percent but tear strength will improve to about 21 pounds. As part of a composite, the fabric does not interfere with low-temperature flexibility or adhesion of the liquid and, as the roof moves, the stress does not rupture the membrane. Instead, the force conveyed into the system, maybe 1 inch or more away from the crack or joint, via the fabric. That 35 percent elongation of movement extends over 1 inch on each side, allowing for 0.7 inches of movement capacity, far exceeding the 0.25 inch provided by the thicker coating described above. The dynamics of a membrane require that the coating/resin remain flexible, making good low-temperature flexibility a must and that the fillers do not interfere with the action of the fabric. These design factors are why most membrane systems rely on premium coating/resins as the binder.

As simple as it is, the use of fabric in liquid-applied systems is a game changer in terms of reliable performance. Most often, this approach has been applied to flashings, details and repairs within typical coating applications. Coming into broader use are liquid-applied roofing systems, or liquid membranes, that are fully reinforced. Not only is long-term crack bridging better with these systems, hail and impact resistance is also often greatly improved, as well. Liquid-applied membrane systems may be used to retrofit leaking or otherwise compromised roofs when a coating application would not be indicated and can perform an important role in new roofing when complex layouts of rooftop equipment, protrusions or irregular shapes make a seamless system preferable. One unique feature of many liquid-applied membranes is they are “breathers;” that is, they have a permeance well above 1 US perms, indicating they allow the release of water vapor. They are frequently user-repairable and do not require special staging or lift equipment, making them perfect for in-house maintenance crews or high-rise applications.

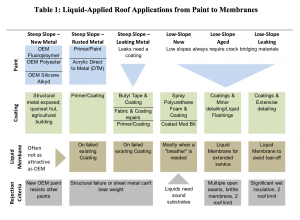

Performance Expectations Lead to Protection Level

The overall condition and performance expectations of an existing roof provide the basis for what level of protection is needed. Only occasionally can that be satisfied with paint or a thin coating. Much of the time, the roof will need some repairs while the field of the roof will still be functional and can be improved by a coating application. More severely leaking and deteriorated roofs often indicate the need for a membrane system, as well as a requirement for extra impact resistance or a longer service life beyond what a coating can provide. Table 1 below summarizes the overall selection and use of liquids while also illustrating some cases for rejection of a maintenance approach. The overall pattern is to move diagonally from paints on the upper left for less challenging applications, to coatings, and then to membranes on the lower right as the application becomes more challenging—starting with new steep-slope metal roofs and reaching to failing low-slope roofs. In this manner, the cost and benefits of liquid-applied systems can be matched to most any situation.

Be the first to comment on "Paints, Coatings and Liquid Membranes"