For centuries, copper has been used as a roofing material because of its ease of installation, adaptability to simple and unique designs, resistance to the elements and superior longevity. Copper’s warmth and beauty complements any style of building, from Gothic cathedrals to the most modern museums and private residences. Its naturally weathering surface, whether in a rich bronze tone or an elegant green patina, is a clear indication that the building owner will only accept the very best.

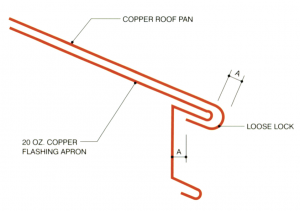

This detail indicates a method for terminating a copper roof at the eave. The fascia trim is bent to extend onto the roof deck to become an integral flashing apron nailed to the roof. The copper pan is secured to the apron lip to achieve vertical restraint. Horizontal movement of the copper roof sheet is accommodated by the loose-lock fold of the pan over the fascia lip. Click to view a larger version.

IMAGE: COPPER IN ARCHITECTURE–DESIGN HANDBOOK

Calculating for the potential thermal movement of sheet metal is easy. Simply multiply a metal’s coefficient of thermal expansion by the metal’s expected temperature change by the length of the piece. Remember: It’s not the air temperature we’re considering; it’s the temperature of the metal. Anyone who’s touched a metal roof or the top of their car in the summer knows it gets significantly hotter than the air!

An example based on a 10-footlong piece of copper:

- 10 feet (typical flashing piece length) x 0.0000098 per degree F (copper’s coefficient of thermal expansion) x 200 degrees F (possible metal temperature change from coldest winter night to hottest summer day) x 12 inches per foot = 0.24 inch. In this case, the calculated movement is a little less than 1/4 inch.

Remember, the coefficient of thermal expansion depends on the type of metal you are using. Aluminum expands and contracts more than copper, and most steels move less. Series 300 alloy stainless steels are very similar to copper in movement, or expansion/ contraction rate. Naturally, temperature change is dependent on building location and exposure to the elements. Many professionals feel comfortable calculating the design movement with a temperature change in the 175 to 200 degree F range, but it’s the project architect or engineer’s responsibility to determine if this is adequate.

Modern rollforming equipment allows contractors and manufacturers to make very long panels, so potential total movement is even more significant.

Let’s investigate one type of common flashing design—in this case, at the eave, which is relatively simple but can easily be installed incorrectly:

- Based on the previous formula, with roof panels that are 20-feet long and installed at a temperature between the hottest day and coldest night: 20 feet x 0.0000098 per degree F x 200 degrees F x 12 inches per foot = 0.47 inch.

Having one of the largest copper roofs in the country, the historic Kingswood High School, Cranford, Mich., recently underwent a massive $14 million roof-restoration project. The copper-clad roof is comprised of batten seams on the upper slopes, interior gutter with internal rainwater conductors, and standing- and flat-seam panels on the eaves. An embossed

copper fascia and copper soffit panels complete the system.

PHOTO: QUINN EVANS ARCHITECTS

Through the years, countless thermal cycles and resulting stresses caused by expansion and contraction can take their toll. In the long run, something will fail. In some cases, work hardening of the metal can occur, causing it to crack or tear. In other cases, fasteners, such as those used to attach cleats, work back and forth, ultimately pulling them out of the substrate.

It’s easy, however, to avoid these problems. To ensure maximum performance of the roofing system, just follow the recommended design principles; understand how the different pieces of the system interact; and don’t cut corners. With a time-proven quality material like copper, proper workmanship and attention to detail can create a beautiful roof that could last the life of the building.

Learn More

For more information about architectural copper and roofing systems, visit the Copper Development Association’s website.

Be the first to comment on "Planning for Thermal Movement: An Essential Element of Copper Roofing Design"