Rick Briggs is in his element. The retired Air Force major has just spent the better part of the afternoon chatting with a steady stream of military veterans and their families, all of whom have come to get a closer look at Camp Liberty, a rehab facility of sorts designed to help wounded soldiers and those suffering from brain trauma.

Camp Liberty, Brooklyn, Mich., is a rehab facility designed to help wounded soldiers and those suffering from brain trauma.

Just last year, Briggs recalls, Britani Lafferty, a 29-year-old veteran who spent time in Iraq as a combat medic, visited the Camp Liberty site. Suffering from debilitating physical and mental wounds from her tour, Lafferty tried countless medical treatments to no avail. Desperate for something that might work, Lafferty turned to the healing power of nature. Invited to spend time at Camp Liberty, Lafferty tried her hand at deer hunting. From a blind overlooking the Raisin River, Lafferty bagged her very first buck. And for Camp Liberty, it marked the first successful hunt for their program.

To Briggs, the moment symbolized that Lafferty could overcome her own afflictions, that she was still able to do things without the help of others. This is the sort of therapy Briggs and the Camp Liberty project hope to impart. “I know vets who are really dealing with severe difficulties,” Briggs says. “They don’t want to be around people. They won’t go to a mall. They won’t go to a movie. We have actually gotten them out here and back to where they can get out and start doing stuff.”

And that’s Camp Liberty’s ultimate goal. “When we get out here doing recreation with guys, it gives them the opportunity to listen and realize that PTSD is treatable,” Briggs adds. “These guys don’t want to believe it. They don’t want to think about it. They don’t want to admit they’re dealing with it. ”

The story of Lafferty is just one example of what Briggs thinks could be a new way to tackle the effects of traumatic brain injuries (TBI) to the body and mind. With the construction of a new program facility, scheduled to be completed by the end of the year, the full vision of Briggs and his childhood friend Allan Lutes is within reach.

Lutes and Briggs aim to construct a wilderness recreation facility focused on helping military veterans recover from debilitating injuries, brain trauma, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Frustrated by the lack of attention paid to veterans (just two years ago, Michigan ranked dead last in the U.S. in military spending on vets), the two vowed to make a difference. And after years of planning, preparation and fundraising, the project, which is located just a few miles from the Michigan International Speedway in Brooklyn, is nearly complete.

From hunting to fishing to kayaking, Camp Liberty offers veterans a quiet, tranquil location where rehabilitation can flourish.

With the help of volunteer crews, Lutes and Briggs are overseeing one of the last steps of the project, the construction of a 2,880-square-foot, handicapped accessible lodge that has taken shape over the past five months. Upon completion, the three-bedroom, two-bathroom structure will allow injured veterans and their families to lengthen their stay and take advantage of all of the outdoor activities the massive site has to offer—and it won’t cost them a cent.

Amidst this huge habitat stand 10 state-of-the-art hunting blinds and wildlife observation towers, all fully handicapped accessible. Along with guided hunting expeditions, the veterans can fish in the nearby Raisin River, hike along numerous nature trails, and enjoy the serenity of a reflection area and outdoor chapel. From hunting to fishing to kayaking, Camp Liberty offers veterans—particularly those who have suffered injuries in combat or are challenged by traumatic brain injuries or post-traumatic stress disorder—a quiet, tranquil location where rehabilitation can flourish.

“Hunting is just a small part of what we offer here,” Lutes notes. “Every inch of this facility has been thought through as a way of something that is going to make someone feel comfortable, feel at peace, feel part of nature, and be able to reflect on their life.”

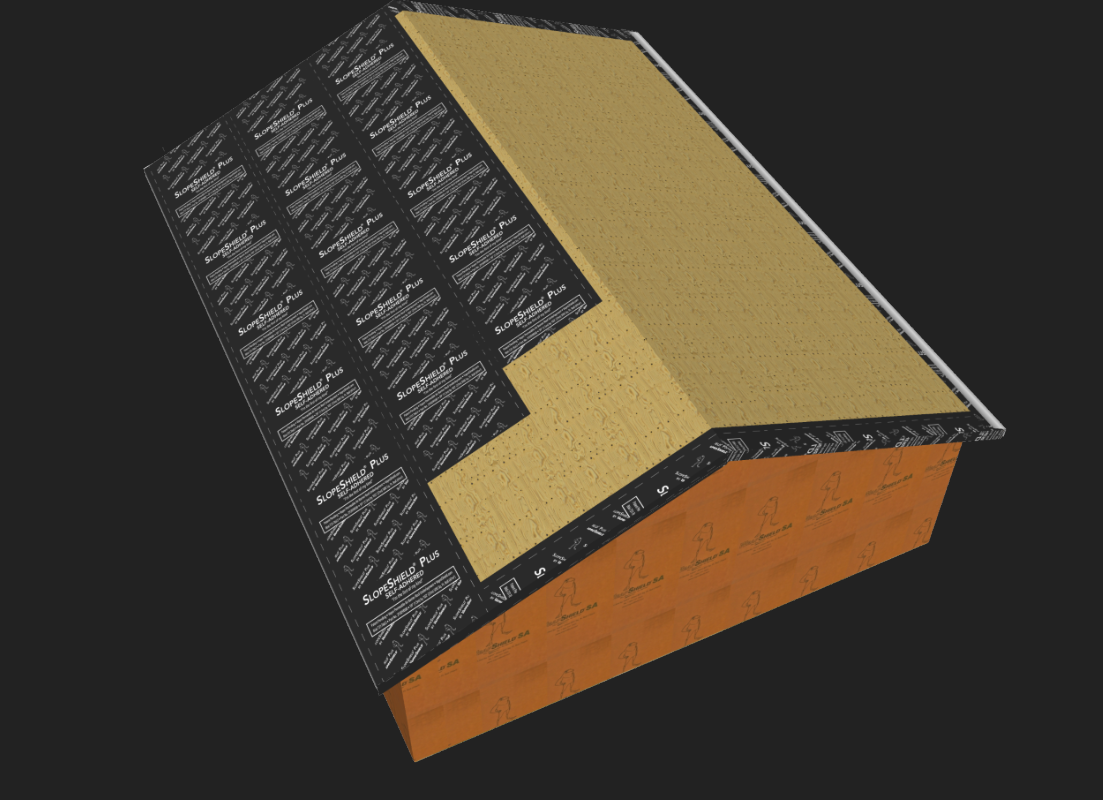

An ambitious project like this doesn’t just happen, of course. The financial barriers would be too daunting for most people, even if they were smart enough to come up with such a unique vision. Briggs, Lutes and the Camp Liberty team have raised close to $300,000 toward their building projects and have recruited volunteers to help with completing the site’s projects. The primary contributor, Lutes adds, has been the Eisenhower Center, the country’s leading brain injury facility, which has donated more than $200,000 to the project. Among a bevy of donors, Atlas Roofing Corp. has provided almost $30,000 in building products for the construction of the program facility, including the ThermalStar Radiant Comfort in-floor heat panels that will regulate heating within the complex, ThermalStar LCI-SS insulated structural sheathing, AC Foam Crossvent Insulation roofing product, WeatherMaster Ice and Water Shield, Gorilla Guard EverFelt Underlayment and Pinnacle Pristine Green Shingles.

“I think the right word [to describe his reaction to the financial support] would be overjoyed,” Lutes says. “Overjoyed that other people have bought into our vision, that other people have seen the value and need for helping our veterans and to help people who have mobility issues enjoy the outdoors. I mean, that is really heartwarming.”

Atlas Roofing Corp. has provided almost $30,000 in building products for the construction of the program facility.

Zezawa is among a steady stream of volunteers who have lent a hand. Throughout the summer, members of the Jackson County Habitat for Humanity jumped on board to lead the construction of the program facility’s foundation, structure and roof. The crew, ranging in age from 60 to 93, spent the better part of the summer in what crew chief David Behnke called “a wonderful experience”. “If you can’t get behind this project, you can’t get behind anything,” he says.

A.J. Mikulka is a 33-year old Army National Guard veteran who has been hunting since she was a kid, learning how to carry a shotgun from her father. She is not unlike many of the veterans that Lutes and Briggs hope to help. On Aug. 9, 2007, Mikulka, serving in Mosul, Iraq, was in the midst of helping to train Iraqi police when the station started taking enemy fire. When she stepped out from behind a barricade, insurgent forces launched a rocket-propelled grenade. “It was a direct hit. It took my leg clean off,” she recalls. Mikulka now walks with a prosthetic, which is attached to her leg just below the knee.

Her physical recovery didn’t take nearly as long as the emotional recovery, though. Mikulka believes the mental recuperation offered by Camp Liberty will have a “profound effect” on wounded veterans like herself. “There’s always going to be stuff that you deal with [emotionally],” she says. “I know a lot of [injured veterans] who are still dealing with it years later. The hard part for me was [dealing with] the loss of career.”

Lutes and Briggs hope that Camp Liberty will be a place that people like Mikulka can come to heal and feel “normal again.” Research supports their hunch. A 2013 study by the University of Michigan indicated that time spent in nature can improve cognitive abilities, particularly for those who suffer from post-deployment issues. “The research clearly shows that extended outdoor recreation helps combat-injured veterans,” Briggs notes. “And the more severe their injuries, the more significant the outcomes.”

It’s nearly impossible to not come away impressed by what has happened in this remote area in southeastern Michigan. Roger Barnett, a 66-year-old veteran, who was “in the mud” in Vietnam, spent an afternoon with his wife Dottie chatting with other visitors at a recent Camp Liberty open house. “It’s just really great to have for these guys with disabilities,” Barnett states. “It’s all set up for them. It’s all set up for recreation, for them [to have] some kind of an outlet and get together and spend time in front of the fireplace and relax. It’s great. It’s just what they need.”

Now, Briggs and Lutes are just antsy to get the construction completed. While they enjoy bringing attention to Camp Liberty, raising funds and chatting with the press, they’re eager for the property to begin hosting those who need it the most. “We hope to be able to help the veterans realize that they may have a TBI issue or a PTSD issue and that there is a treatment option that can improve it without them sacrificing their jobs, their military rating or their relationships,” Lutes says. “We’ve proven to ourselves that what we do can change lives for the better.”

Be the first to comment on "Manufacturer Donates Roofing Materials and More to Camp that Assists Veterans Suffering from Brain Trauma"